https://twitter.com/MarioEmblem_2/status/1676009845235896320

It's not just color, everything has a subjective experience only knowable by the haver. What does joy feel like? What does a feather on your finger feel like? What does the color blue look like?

These experiences are called Qualia. In the comic above, the smaller bear has a different quale of the color blue than the larger bear does.

Phenomenology, it's a hell of a thing.

Also, ironically, shows why total subjectivity is BS. Even with different qualia, the bears all agree on the color (since the object being perceived is the same in either case).

right, regardless of what each person perceives and interprets, the measured wavelength will be the same

Hegel's whole thing: subjectivity is absolutely true but the relation of 2 subjectivities is absolutely objective. Just like velocity and location in physics.

are they really unknowable though? obviously we don't have a deep enough understanding of neuroscience and consciousness to perfectly comprehend the full chain of physical phenomena all the way to subjective experience, but we understand a lot of it, and it mostly seems consistent from person to person afaik. like blue light interacts with a specific type of cone in the retina, producing specific neural responses, etc. etc.

Like you can argue maybe the inner mechanics of the mind mean we are experiencing the colors differently and just assign the same name to it like in the comic, but is there any evidence of that? or is it just mysticism trying to fill in the gaps of our limited understanding of how the mind works.

The concept is about the sort of abstract perception, like the actual final form that gets perceived by the mind, but the whole thing is just one of those pointless philosophical cognitohazards that are like the equivalent of XKCD's "nerd sniping" bit, just shit that's weird and pointless and unsolvable.

Like does the final processing step that is the mind's perception consistently ascribe the exact same perceptive values to a given color or sound that other people do? Maybe, maybe not, because we don't know what mechanically is happening to create that phenomenon, we don't know how consistent the processing in the visual neurons is across individuals, we don't even know what that perception is. So maybe for one person the color blue gets coded as a certain specific voltage or whatever when it transitions from the image processing bit to the consciousness bit (if that's even a distinction that can be made at all), and for another it's 1% different or a different frequency or whatever, but would that even change anything? It's still remaining consistent before that, and it goes along with all the cultural stuff attached to the color, and it clearly works consistently, so it's kind of just a nonsense question that's trying to sound deep.

Like we're talking about possible unknowable differences in systems that developed to sort of chaotically brute force their way into consistency and adaptability. So maybe "blue" gets stored and processed slightly differently between individuals, but we can also see that in every perceivable way it ends up with the same result. So the answer to the question is that it's the wrong question to ask in the first place: blue is always blue because it will always have the properties and associations of blue and those are consistent across people because they're the product of systems that plastically shape themselves to be consistent, and any differences are clearly not materially noticeable if they even exist at all.

I could just as easily ask "what if we all actually have the same favorite color internally, but due to differences in perception ascribe it to different frequencies of light?" and it would be just as valid a question, but even more nonsensical on its face.

blue is always blue because it will always have the properties and associations of blue and those are consistent across people because they're the product of systems that plastically shape themselves to be consistent, and any differences are clearly not materially noticeable if they even exist at all.

Good points, though people do not perceive blue the same in the sense of same properties and associations. Humans are no idealized platonic digitalized humans. Being human is concrete materiality and that means that we are each different and bring our own upbringing and past with us.

Exactly how it all works can (almost certainly) be ascertained. If organisms who care enough to know survive long enough in the right conditions.

It certainly seems like everything can ultimately be quantified, though I am a determinist personally.

It is the difference between subjective reality and objective reality. Subjective, by definition, means it depends on perspective (a subject). Objective is the opposite, it does not depend on perspective, it is true for all perspectives.

In a certain capacity it is possible to know something subjective. If you are looking at something — say, a bird — that I can't see from where I'm standing, I can move to where you are standing, and be able to see the bird myself from where you were standing.

But location is only one level of abstraction from which we understand perspective. Time is also a factor. What if, in the time it took for me to move to your spot, the bird flies away, and I miss it? Then it becomes clear, I didn't have the same perspective that allowed me to spot the bird.

This path of further specifying the extreme detail which makes up a subjective experience ultimately leads to impossible requirements like being in the same mental state, having had enough sleep the night before — in the last resort, having lived all the same experiences until that present moment, and having an identical physical body throughout the whole process. There can be no true knowledge of a subjective experience without experiencing the exact same thing, in all of the specificity that entails. In a word, without being the same subject.

We can know objective facts which are independent of perspective, such as empirical measurements like temperature and pressure, all the way up to more complex facts like "we live in a society of commodity production and exchange." But those are objective because different observers can verify them empirically, like the color blue in the OP's post.

An additional thought... the history of science is essentially the history of finding objective facts, facts which are true regardless of perspective. Even physics, being perhaps the most basic and immediate field of research, has struggled to find an end to the manifold perspectives which can overthrow what we had thought were objective facts.

One can of course point to the discovery of the round earth, or of heliocentrism. But it goes further.

We thought we were pretty smart when we figured out classical mechanics and thermodynamics. Lord Kelvin famously said,

"There is nothing new to be discovered in physics now. All that remains is more and more precise measurement."

This obviously turned out to be false because, when you look really closely at stuff, quantum mechanics starts to change everything. What we thought were particles with definite positions and moments, at last revealed themselves to be indeterminate wave-ish things.

For that matter, general relativity a few decades prior had upended our most basic notions of time and space. We thought we were safe saying the Sun is at such-and-such position 150 million kilometers in blah direction, and it is 5 billion years old, etc etc. But because the speed of light is constant regardless of your motion, this forces us to accept that other observers might observe the Sun somewhere else and perhaps a different age than what we perceive. Thus the name relativity; there is in fact no objective frame of reference. In science we use the inertial frame as the default, but it is arbitrary and not intrinsically more correct than the frame on the event horizon of a black hole.

Even in my previous comment, where I listed temperature and pressure as objective, to claim those as objective it is necessary to specify (implicitly in my case) some location and time which give validity to calling them objective.

So it is always the case, for any objective fact, that it depends on a set of assumptions about what is sufficient to call a perspective "the same" enough that it can be said that two subjects share a perspective. This abstract sense of shared perspective is what gives rise to "objective" facts, which may in fact not be objective for the whole universe. But as a practical matter it is usually only necessary to assume things which are common to all, such as being on Earth, living in 2023, being a human, etc.

An additional thought... the history of science is essentially the history of finding objective facts, facts which are true regardless of perspective.

I agree with basically everything you've said throughout your post, but I do want to emphasize that even this got thrown out the window in the mid-20th century with the work of Kuhn and Quine. Scientific realism is currently trying to mount something of a comeback, but some rather compelling work in history and philosophy of science says that the notion of objective facts needs to go out the window.

Interesting, I'll have to look into those authors you mentioned. I agree, there does seem to be a shift away from a clean separation of objective and subjective, toward a more refined attitude of true given these assumptions, i.e. an emphasis on the scope of validity for a given fact, and never believing for a second that we've found the absolute end of science, scoped out all of the hidden assumptions or miscategorizations we didn't realize we held.

You're getting very close to Quine's confirmational holism there. Cool stuff all around.

In that we can't know it with our current tools, theories and methodologies.

Jesus christ, this site just goes completely downhill when anything philosophical is involved.

We aren’t talking about the physical stimulus itself! We are talking about subjective internal experience! Just because the same area of the brain correlates to a specific color or whatever doesn’t mean you experience the same thing. Hard problem of consciousness

Not even taking into consideration the STEMlord hurr-durr philosophy is useless takes.

Once again for emphasis:

THE STIMULUS IS NOT THE SAME THING AS YOUR EXPERIENCE OF IT

People may very well experience the same color differently, and we would have no way of knowing. There will always be a subjective gap that can’t be bridged. We see the same wavelength but we cannot know if we experience it the same way. Color theory and the physics of light is completely irrelevant here.

It’s not that you see red as blue; you see blue as blue, that’s not the argument here. Everyone sees blue as blue. We just might not have the same subjective experience of it. This is like baby level philosophy shit, I would have thought it would be quite simple to understand.

this site just goes completely downhill when anything philosophical is involved

sadly very true

I completely agree with you that the internal stuff matters. However so often people say that people might experience red as blue or something like that which is a bad thing to say (and I hear often, and it is bad for multiple reasons, but especially that it shines the spot light away from the interesting bit which you focused on rightfully and introduces some tackled web to uncurl).

That said the physiology of bodies means and how light interacts with them means that two colours couldn't arbitrarily be switched in their internal mechanic. Cause they would be different experiences for the sensors our body got. Which sometimes gets ignored by some people engaging in philosophy who don't care about physical bodies and are too idealist and non-materialist.

You pointed to the correct thing though.

Yeah the original tweet makes sense. I don't get why this is a dunk

Got a lot of STEMlord-brained dum dums in this thread...

i dont think you are engaging with the actual thinking going on and instead are being like "but what about the fact that we can never truly know anyone else!!!" it's easy to understand. light is a phenomena that is pretty well explained in physics and with other "philosophical" or logical evidence. we're not all seeing different shit even if it's interesting to think about

I had a terrible night’s sleep so I’m gonna be grumpy here

Read my comment again. It is literally not possible to prove this either way, that’s the whole point.

Yes, you are seeing the exact same wavelength as everyone else. No, this has nothing to do with the argument. No amount of incessantly pointing to the physics of the stimulus is going to resolve the question.

I don’t think you understand that this has literally nothing to do with the physics of light. It’s honestly amazing that you point to this even after the countless clarifications that that is not the point of the discussion. No one is questioning the physics of light. We could perfectly well be seeing different shit. Consciousness and subjective experience, one of the greatest enigmas to this day, it’s anything but understood. Color is just a proxy for this discussion. You could make it about sound or pain or basically anything.the question is “do we have the same sensory experience for the same stimulus”? You can explain the physics of light every step of the way and it wouldn’t even touch on subjective experience.

In summary:

- Is the physics of light well understood?

Yes.

Are our eyes physically structured basically identically?

Yes.

Is the stimulus, physically speaking, a constant for both observers?

Yes.

Are the physical properties of the light hitting the retina the same for both?

Yes.

Is our internal sensory perception universal?

I don’t know, and if you do, you should get it published and live off the coattails of one of the greatest achievements in scientific history for the rest of your life.

da physics of the eye is also da same and our brains are all built roughly the same so whateva

If we perceive senses the same way, why do some people disagree about what colors go together or if something tastes good?

If the internal experience of the sense is the same, why would anyone have different tastes?

When people like different things, is it entirely arbitrary? Or is it because they perceive the internal sensation differently?

I didn’t know we were relitigating this, but this is a philosophical concept that is related to physics but which cannot be explained by it, not because of anything supernatural, but because that’s how language works

Boba Kiki test

colors could be tested the same way, just latch a brain helmet on and see how they react when seeing red/blue etc

I've wondered about this, but it's the kind of completely non-falsifiable thing that isn't relevant beyond a philosophy classroom.

yeah. And completely impenetrable to scientific explanation, because they'll just go a level deeper. "how do we know we're all seeing the same blue?" "Oh, well blue light has a certain wavelength." "but we could be experiencing that wavelength differently!" "Well it doesn't seem like we are, the same cones in our eyes respond in the same way to that wavelength of light." "Well maybe its a difference in the brain then?" "It doesn't seem like that's true either, certain regions of the brain react in similar ways when shown the same light." "Well maybe our consciousness just feels it differently?"

Completely useless discussion tbh.

Completely useless discussion tbh.

Questioning what facts are "objective", and how, is far from useless. That is the central question of Marxism, the analysis of "objective" categories which in fact have concealed subjectivity, most notably the historical specificity of certain categories like value.

Questioning what facts are "objective", and how, is far from useless.

well good thing I didn't say that then. I'm talking about this pop philosophy tier bullshit that's like "what if we all like, see colors different, maaan?"

Its not inherently a useless category of topics, though I think it gets navelgazey very frequently, just that the pop culture iterations of it that go around, like the OP, aren't interesting or useful

understandable. I don't mean to be overly combative, just gets tiring I guess

Have a good sleep

Idk, man. Once you start getting into the physics of a thing, it becomes difficult to argue "Some people just perceive the light frequencies of blue and red as opposite". These aren't strict interchangeable experiences. If you actually did experience a different spectrum of light, we could absolutely recognize as much.

We've got the doppler effect to consider, wherein traveling at different speeds can change the perception of light, but in a recognizable and repeatable direction. I can red-shift by slowing down and blue-shift by speeding up. But I can't do the reverse. Neither are we finding people who can just start perceiving ultra-violate or infra-red thanks to genetic drift.

We also have plenty of evidence that language informs ranges of color. As evidenced by a study done in Namibia whereas a tribe that does not discern between blues and green with different words, rather the English word for blue is often considered a variant of green through the tribe’s language, was given a color wheel of green squares and one blue square. Those in the study had a difficult time distinguishing which square was blue, however, were quick to differentiate another color wheel with all squares containing the same shade of green, except one shade that was slightly different. The English speakers in the video had a much more difficult time distinguishing the different variant of green.

So this sort of thing is falsifiable on several fronts. It just doesn't hold up at the degree the artist is describing.

No more than someone saying "I experience traveling 15 mph as though I was traveling 5 mph". Like, that's just not how things work.

None of this is a refutation of the idea that someone could experience the color spectrum in an inverted fashion. Red- and blue-shifting would just have their warming/cooling reversed along with everything else.

Red- and blue-shifting would just have their warming/cooling reversed

No. Because these are magnitudes. A red-shift would not cause you to perceive things in reverse any more than someone with a handful of beans would be perceived as adding beans by taking them away.

You are smarter than this, come on. This whole time I think everyone has been clear that we're talking about the sensation itself and not the stimulus itself. We are not talking about heat in terms of the vibration of molecules but in terms of someone's internal experience of something being hot. We aren't talking about pressure in terms of psi or atms but the tactile sense, such that someone with no sense of touch would be irrelevant to that conversation even though we recognize that the physical phenomenon of pressure applies just as much to them as anyone else and they'd have been squished if they were in the Titan sub just as quickly as those sorry jackasses were.

Just to make it easier to put in words, let's phrase it in terms of sound (afaik this is the original observation of the doppler effect anyway). If someone's perception of pitch was reversed, such that flies buzzing made a low-pitched noise and earthquakes were mainly high-pitched noise, the terms "high" and "low" pitch are not said in correspondence to the greatness in Hz of the soundwave, but the subjective experience of the sound (which incidentally in this thought experiment has an inverse relation to the Hz). Therefore, if someone with this condition has a fly fly towards them, the doppler effect dictates that the Hz of the sound waves would be higher than a fly flying in a vertical circle where the midpoint of the listener's ears are the center. Because the Hz is higher, and we know that this person experiences higher Hz as lower pitch, the fly would have a lower-pitch buzz while it was flying towards them. Likewise, flying away would produce soundwaves of a lower Hz and therefore a higher pitch to that listener.

So in the original case with color, we know that red-shifting would produce a cooler color because the stimulus is just the stimulus and the specific mechanism by which it was formed has no bearing on how it was perceived. In normal humans, there is no difference between a shade of yellow and a shade of green that gets red-shifted to yellow, the end result is the same, so if we inverted someone's perception, this would carry over.

I completely forgot, a crude approximation of this can be seen with a negative filter on a camera! Red-shifting doesn't just magically make things redder on a negative filter because it has "red" in the name, because the negative filter interprets the warmer light waves as being cooler.

It's really funny that you use the doppler effect for this example, as it seems the absolute worst version of this possible in my mind. When things are low pitched enough, we can literally hear the movements and connect them to the object we see moving, which gives an external anchor to the problem of sebjectivity. We KNOW that low pitched things sound that way ebcause it would otherwise result in things not align visibly with the vibration/back and forth movement.

If that was historically used, then it's funny because it's the weakest form of this argument.

When I mentioned history, I meant that the sonic doppler effect was discovered before the visual doppler effect: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3743612/

I think just because it was more convenient to measure, since the idea came from a simple mathematical observation about the properties of waves. I guess it also could have come from watching buoyant objects move in water, since a boat's wake is partly a manifestation of the doppler effect as well.

If you want an actual historical text regarding the arbitrariness of sensation, the first of Charles Berkley's Three Dialogues covers it well.

Anyway, I don't see your point -- or rather, you keep missing mine -- we can say there is connection between low sounds and slow oscillation, but ultimately the correspondence in timing has only an arbitrary relation to the sensation of pitch itself, just as a blinking light being aligned in time with our experience of it does not cement the "objectivity" of the color we perceive it as. Whatever the timing is, it can be "colored in" with whatever sensation we stipulate.

Like, just think for mere seconds about the fact that synesthesia exists. Sounds can be experienced as smells, and it's an incident of evolution that we don't experience them that way.

Sorry I think you got the wrong comrade, this was my first reply. I agree with you, I just think that the high and low pitch is the worst possible choice for the argument. Like hot and cold have no external comparison, but the qualia of high and low pitch is very literally connected to another sense (in this case the sight of a low pitched subwoofer or such). Even when moving and causing the Doppler effect to you as observer, that anchor still exists just with a shift that is also externally explainable.

Sight, hot/cold, all kinds of smells, all have a sense of disconnection between sense and qualia. How you hear complex sounds (filters or such) introduces qualia

But remember, we actually agree, I just think your example wasn't good to convince anybody else

I think it's more fundamental than physics. There is no physical theory of human consciousness, experience, and perception. Only theories of how our physical bodies work, in mechanical terms. Of course most socialists are materialists and accept that matter forms the basis of reality, but that doesn't make subjective experiences explicable in objective, abstract terms.

There is no physical theory of human consciousness, experience, and perception.

No, but the human brain is still a physical/chemical machine and it still needs to process a set of homogeneous information. At some point you have to identify the part of the body that's doing the conversion from photon to information and say "Look! See! Brain X is doing this but Brain Y is doing that."

In some of the experiments above, we absolutely can do that. In others, say - by recreating the structure of the eye and realizing the image we get is upside down - we can simply infer that the brain has to do some amount of work to correct for things universally.

But if you just assert, carte blanche, that where you see a "2" I see a "3", and wave off any argument as a qualia... no. That's just not how things work.

that doesn't make subjective experiences explicable in objective, abstract terms.

We can engage in objective measurement of subjective participants and hunt for inconsistencies in experience. We can put a filter over each person's eye, knowing that they'll only experience X+1 and X-1, but not X, in order to factor down what each person does or doesn't perceive.

But these artifacts of consciousness come from somewhere and are processed/stored by something. And these biological machines do all operate on the same physical principles.

So, baring some real evidence to the contrary, it doesn't follow that one guy just sees a 400nm wave as a 700nm wave.

In some of the experiments above, we absolutely can do that.

Until and unless we can image thoughts down to the detail, no, we can't do much more than "this region of the brain lights up when it sees something".

we can simply infer that the brain has to do some amount of work to correct for things universally

We can infer that people are able to navigate and make sense of the world regardless of the inverting effect of the eye. We cannot infer the experience of seeing nor explain it in physical terms.

if you just assert, carte blanche, that where you see a "2" I see a "3", and wave off any argument as a qualia

That is not the argument at all.

it doesn't follow that one guy just sees a 400nm wave as a 700nm wave.

That is not the argument either. It is a question of the experience of perceiving the color blue. Note that in the OP, the observer can consistently identify a 400nm wave regardless of how they perceive it, as long as that perception is consistent. It only needs to be consistent for that observer, not between observers.

Until and unless we can image thoughts down to the detail

You don't need to image thoughts of color to recognize common ability to distinguish them any more than you would with shapes or quantities. These are quantifiable metrics, after all.

We can infer that people are able to navigate and make sense of the world regardless of the inverting effect of the eye. We cannot infer the experience of seeing nor explain it in physical terms.

We can, once we understand the mechanics of light passing through a camera obscura. These questions aren't trivial to answer, but they are answerable. What's more, we have already answered them.

We cannot infer the experience of seeing nor explain it in physical terms.

We can and we routinely do. That gets us into the language of colors and the way description shapes perception. We can consistently reproduce the phenomena of perceived color by language demographic.

It is a question of the experience of perceiving the color blue.

The experience is still a consequence of a mechanical effect. Namely, the brain processes certain frequencies of light in a particular manner. The only way to conclude that I'm seeing a 300nm shift in the color spectrum relative to you is to explain the mechanical gap in our cognition. And if I'm that far off the mark, I should be able to measure the difference relative to the midpoints very easily. This is all quantifiable. It shows up in medical diagnosis as various forms of color blindness or hyper-sensitivity.

OP asserts a dramatic shift in perception that absolutely should be something a physician looking for it can spot. The trick OP plays is that they're only working from a single data point (a very particular shade of red) rather than a full spectrum of colors. As soon as you lay out a rainbow for the child, you'll recognize the difference between their perception and the human standard.

The trick OP plays is that they're only working from a single data point (a very particular shade of red) rather than a full spectrum of colors. As soon as you lay out a rainbow for the child, you'll recognize the difference between their perception and the human standard.

Not to be rude but I don't think you understand the post if that is your stance. Adding more colors would not change the scenario at all. If your conscious, internal experience of all the colors is like mine except rotated by one (so that my ROYGBIV is your OYGBIVR) we would still be in 100% agreement about the color of any test object. The experience of color does not affect the test result, as long as it is consistent for each of us: whatever you experience in your mind is always the same in response to 400 nm light, and the same for myself, although my experience is not necessarily identical to your experience.

The above example is not equivalent to "I see 500 nm light and you see 400 nm light". We would both agree on the physical property of the light. The experience is what could, in principle, differ.

How can RGB compose properly edge colour like yellow? Intensity curve would be reversed. Why only the visible spectrum inverted centered on median human visible colour? This is a very human-centric way to think. "Inversion" is not a universal concept.

If your conscious, internal experience of all the colors is like mine except rotated by one (so that my ROYGBIV is your OYGBIVR) we would still be in 100% agreement about the color of any test object

I think color theory demonstrates that this isn't true and it would need to be an inverted rainbow or one of "new" colors in order to stay consistent.

I don't see what's dunkworthy about this unless you think qualia as a concept is dunkworthy, which is fair.

As for the comic, when we say the sky is blue, what we are actually saying is that the sky share a certain optical property with the sea and other objects that we deem as blue. In other words, it's more about the sky's relations to certain objects rather than an intrinsic property of the sky itself or a person's subjective experience of the sky. To hammer this point even further, orange the fruit entered the English language before orange the color, so when we say this crayon is orange, we are very explicitly saying the crayon has an optical property that's similar to a citrus fruit. Likewise, the previous Old English word for orange was geoluread or yellow-red, and it's easy to see why orange the color used to be called yellow-red. In this case, it's the relations of the color orange being between the color yellow and red.

The actual qualia of blue is just a subjective experience with no real way of substantiating as objective truth. But it really isn't that important because subjectivity by definition can't become objective. You'll never truly experience what I experience as an individual subject with my own unique physical makeup, psychological makeup, and personal history, but this shouldn't be world-shattering because you're not me lol. There are objective facts that can be gleamed from what I'm experience. For example, you could hook me up to some machine that monitors my heartbeat and notice my heartbeat going up when I get nervous about something, but you can never experience exactly what I'm experiencing. You'll never be able to replicate my grief over a family member because my relationship between the family member and me which informs my grief isn't something that can be replicated.

This is just the contradiction between subjectivity and objectivity and how to navigate this contradiction. The comic slants towards subjectivity at the cost of objectivity in my opinion, which I guess is dunkworthy.

This is my favorite post in the thread. I don't see how people could have vastly different perceptions of color unless those perceptions were shifted on a scale or something. Most people would say orange is a color between red and yellow, so those three colors are connected for most people.

At best you could say maybe people have a different perception of where the rainbow starts? Like mine starts at what I think is red, but what you think is green. Maybe orange to me is violet to you, so it still seems like a between color, just with purple and blue instead of red and yellow.

Also, camouflage works for most people, so clearly those colors are similar. Really wacky different perceptions probably don't exist. The image shows the child seeing brown as purple and blue as red, which would mean he'd fail certain colorblind tests, wouldn't it?

Wouldn’t camouflage still work? The color of the camouflage would still match the color of what it’s trying to blend in with if you switched the colors.

Colorblind tests measure your failure to distinguish the relation of multiple subjectivities. It can be said that this relation is objective. Color blindness is a dysfunction of the cells in your eye, something much more easily examined than internal experience.

If u don’t wanna read all the nerds talking about phenomenology and qualia just consider this:

Hummingbirds in North America all go to red flowers, that’s why the feeders use red molded plastic. Bees, flies, butterflies and bats all exhibit reproducible color preference when foraging for nectar.

Trees are green, the sky is blue, blood is red, the fruits of the vine are all manner of colors and our sun is yellow.

Rather than engage in a long philosophical endeavor to prove or disprove that we (might not) all see the same thing, why not simply look to every demarcation of brain and eye development and recognize that they are all able to consistently respond to colors without training. Then observe how we are able to differentiate those colors too (and which ones we cannot!) and accept that color perception does not require the neocortex or qualia or discussion to establish amongst sparrows which leaves are emerald or viridian.

Then turn our eye towards ourselves and notice that throughout human history there are only a handful of types of color perception disorders, all with very well understood mechanisms of action. We do not see the profusion of sightednesses that would be implied when we reach back into the record.

So don’t fuck with all that shit. The colors are the colors.

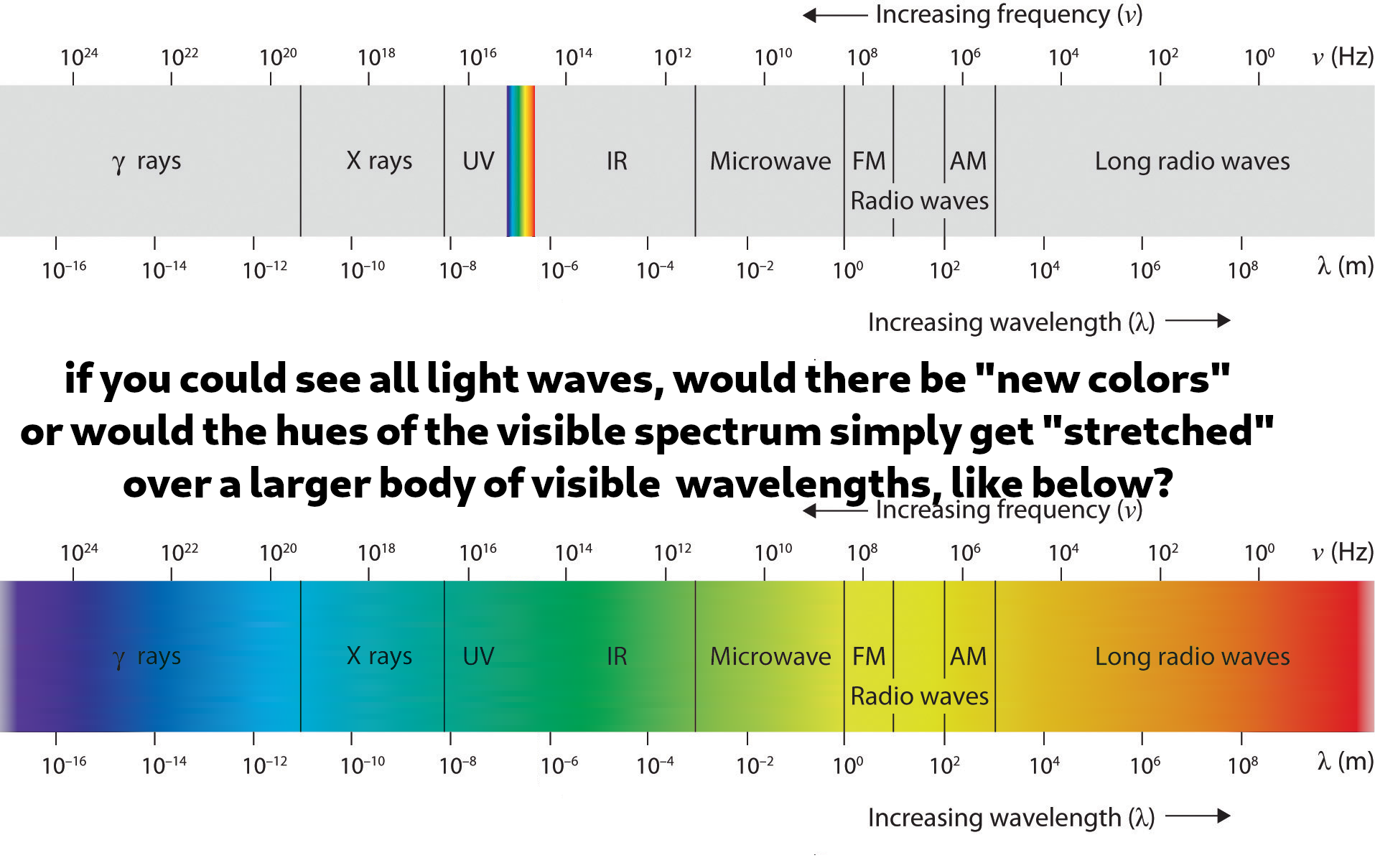

I think the idea being put forward is that the hue distribution could be different from brain to brain while brightness and saturation work the same. That's how the color names and vision disorders could be consistent between people and cultures while individuals still could fundamentally be perceiving different hues than each other. Basically the idea being put forward is that hues are arbitrarily assigned by the brain after the color is perceived while light and vision still work the same. The color you and I call "magenta" regardless of what hue our brain assigns to "magenta" isn't even part of the visible spectrum of wavelengths and is basically made up by the brain to "loop around" the highest wavelength colors with the lowest wavelength colors, and also to provide a contrast with green, which is useful for fruit foraging. But since the hues that we do see "loop around" in a color wheel, despite only encompassing a narrow band of all light wavelengths (700-nm -400nm) then the hues themselves (but not their specific brightness and saturation) are independent of the light wavelengths, and are fabricated by the brain to "make sense of" the light itself. So systematically as long as hues get assigned by the brain to certain wavelengths, and as long as the brain can detect saturation and brightness accurately independent of those hues, people could use the same words for the same colors despite seeing different hues. Colorblindness disorders could be a failure of the eyes to differentiate certain wavelengths of light, independent of what hues the brain would assign to those wavelengths. But yes, you are correct in that none of this matters or can really be proven without knowing more about how the brain assigns subjective qualia to real data coming in from the outside.

Hue = what gets assigned by the brain

Color = our common language for the hues after they've been assigned.

Show

Notice how the square on the left is all different brightnesses and saturations of a given hue (magenta). This includes white and black. All hues can be so bright they become white or so dark they become black. All hues can become so desaturated that they become gray. So the hues are independent of the most important aspects, brightness and saturation. They seem to exist only to contrast wavelengths, and the wavelengths could independent of the hues themselves since some wavelengths don't even get assigned hues (because we did not evolve to see them), and there is a color (magenta) not associated with any wavelength, but nevertheless existing in the mind. If we were able to see the entire spectrum of light, our existing hue distribution might just get "stretched" over the entire spectrum rather than there being "new colors," like this:

Show

Lol if you think I’m reading any of that.

I’m looking at some stuff that’s colors right now, wanna know which ones it is?

ok. I find this interesting but if you don't that's alright. Have a nice day!

If we were able to see the entire spectrum of light, our existing hue distribution might just get "stretched" over the entire spectrum rather than there being "new colors

You could test this by seeing if a parakeet has less color discrimination within the human-visible spectrum

I highly doubt it tho, there would almost definitely be "new colors"

more shades of the existing colors or literal new colors we can't conceive of?

Yeah this is what I would write too if I were NASA trying to hide something

Isn't part of the point of science as a concept to mitigate this kind of thing? Like since we can't know each others' subjective experience, we agree on external, relative variables to measure with instead?

Wavelengths of light have already been mentioned, but the same applies to things like distance and time. Lots of things (like drugs, precious drugs) mess with your experience of time, so we make clocks to measure time in an external fashion so that we can have an agreed upon standard, right?

Your inner experience is often a short-sighted idiot and needs correction from group consensus and NO you cannot reject this truth because of capitalism, you just gotta learn how to read graphs n shit

EDIT: don't take this post too seriously I'm a zoology enjoyer not a philosopher

Yes but have you considered the stress-reduction benefits of pudding brain?

This is the kind of thing that I would think about when wandering the playground in solitude when I was 10 years old.

take the 2nd hit of weed ever in your life and this one resolves pretty quickly

This is what I was trying to put into words earlier. Stuff like camouflage and signal lights wouldn't work if people perceived randomly different sets of colors, they could only possibly see different points along the wheel.

It is also true that certain colors seem to catalyze certain emotional states that aren't always tied to culture or language, so I don't know how that would work with different color perception

I think emotional responses to color have little to do with the qualia itself and is more of a learned social association.

Of course the problem with phenomenology is the assumption that consciousness is a meaningful phenomenon. All action and reaction, including thought and feeling, was predetermined by the iron laws of the cosmos at the beginning of time. The human experience is nothing more than pantomime, doomed to follow its fated course.

I don't really believe this.

It's easy but also very wrong, and actually not really as cool as you think it is. It's IMO an ideological artifact of Enlightenment-era science trying to distance itself from religion in a way it doesn't cause conflict with religious authorities. Worked fine for a while but it's not really the truth.

https://thesideview.co/journal/why-i-am-not-a-physicalist/

But they'd just seen the blue in the picture the same way they see it in nature. Cameras can't capture qualia.

Nothing can prove qualia.

"the philosopher John Locke recognized that alternatives are possible, and described one such hypothetical case with the "inverted spectrum" thought experiment. For example, someone with an inverted spectrum might experience green while seeing 'red' (700 nm) light, and experience red while seeing 'green' (530 nm) light. This inversion has never been demonstrated in experiment.

Qualia are not physical measurements of a physical phenomena, it is how it subjectively 'feels' to experience the perception (measurement) of a phenomena. John Locke's inverted spectrum thought experiment is not necessarily intended to be a falsifiable claim about a real phenomena, but a simplified explanation of an example in differences between qualia between people. Its not a particularly good example, but he was not necessarily trying to claim that that specific case literally happened or will happen (as far as i know). A better example would be the difference between experiencing a view of something red, and the mathematically modelled and quantified wavelength of the light in nanometers. the mathematical model and empirical data does not tell you anything about what it feels like to see the red color, it only tells you what its quantifiable characteristics are, modelled in the form of numbers and symbols. the data alone cannot tell you anything qualitative, you have to at least ask other subjects like yourself to confirm such things. I do think it is reasonable that humans generally see colors similarly, for regardless of your opinion on the problem of consciousness, our experiences are highly correlated to various quantifiable physical phenomena in our bodies. the problem is that there has yet to be established a causal link between physical phenomena and subjective experience.

the problem is that there has yet to be established a causal link between physical phenomena and subjective experience

Qualia is inherently non-falsifiable.

it is a logical concept, not an empirical physical phenomena. it is as non falsifiable as the number 3 or the concept of 'Up'

According to a 2020 PhilPapers survey, 29.72% of philosophers surveyed believe that the hard problem does not exist, while 62.42% of philosophers surveyed believe that the hard problem is a genuine problem.

It Is Difficult to Get a Man to Understand Something When His Salary Depends Upon His Not Understanding It

positivist journal

1950's called they want their dead philosophical movement back.

Well this thread at least brought me to this interesting philosophical concept: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Private_language_argument

By analogy, it does not matter that one cannot experience another's subjective sensations. Unless talk of such subjective experience is learned through public experience the actual content is irrelevant; all we can discuss is what is available in our public language.

Wittgenstein suggests that the case of pains is not really amenable to the uses philosophers would make of it. "That is to say: if we construe the grammar of the expression of sensation on the model of 'object and designation', the object drops out of consideration as irrelevant."